From favored trade status to forced technology transfers, Beijing leveraged American goodwill, market access and corporate greed to become Washington’s most powerful strategic competitor.

Around the turn of the century, the U.S. gave up its market dominance on critical minerals, began mass-importing Chinese goods and exporting intellectual property to access Chinese markets – all while the Chinese Communist Party grew into America’s biggest foe.

“The Chinese have been predatory, and they’ve engaged in criminal acts, theft of U.S. intellectual property. But the story here is not China,” said China expert and Gatestone Institute fellow Gordon Chang. “The story here is that we allowed them to get away with this. We knew what was going on. We’ve known it for decades, and we never really took effective action to stop it.”

Here’s a look back at five times China manipulated U.S. industry and policymakers into more favorable economic terms:

US ALLIES LINE UP FOR TRADE DEALS DURING THE 90-DAY TARIFF PAUSE

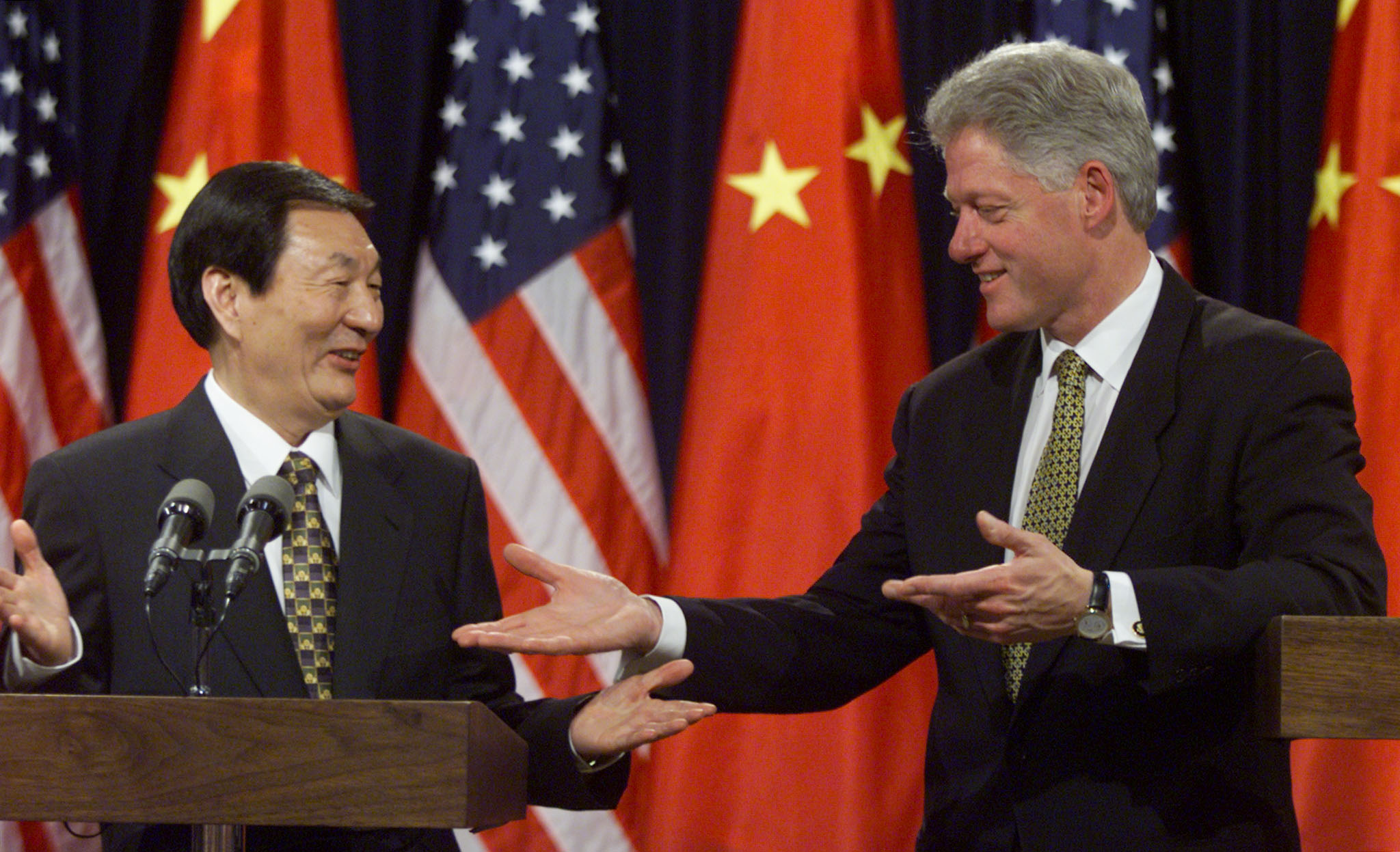

Throughout the 1990s, China lobbied aggressively to normalize trade relations – and found a key ally in President Bill Clinton. By 2000, Congress granted China permanent normal trade relations, paving the way for its entry into the World Trade Organization in 2001.

At the time, China was already the world’s sixth-largest economy, with a population topping one billion. It was a stark contrast from the decades prior, when its communist system had kept the country largely closed off from global markets.

And while China was already known for human rights abuses and heavy state control over its economy, it made vague promises of reform and cooperation – promises that helped win over the U.S.

The U.S. hoped that bringing China into the WTO would check its communist government and accelerate its shift toward a market economy. By joining, China would have to cut tariffs and pledge to protect intellectual property rights.

Clinton wasn’t alone in believing that trade with China would also export Western values. “No nation on Earth has discovered a way to import the world’s goods and services while stopping foreign ideas at the border,” his predecessor, President George H.W. Bush, had said.

China’s WTO accession and Most Favored Nation status opened the floodgates to low-cost Chinese goods. Imports to the U.S. surged from $102.3 billion in 2001 to $426.9 billion in 2023, according to the U.S. Bureau of Economic Data.

In the other direction, China imported around $26 billion worth of U.S. goods in 2001, according to Chinese customs data, compared with $147.8 billion in U.S. exports to China in 2023, according to U.S. import data.

In the 1990s, Congress raised the de minimis threshold for imports to $200 – and in 2016, it jumped again to $800. Under that rule, goods valued below the threshold could enter the U.S. duty-free and without formal customs checks, a system intended to ease low-value shipments but since widely exploited by Chinese e-commerce sellers. President Donald Trump recently moved to eliminate the threshold for Chinese goods, closing a loophole that had allowed billions in untaxed imports to flood the U.S. market.

TRUMP’S TARIFF GAMBLE PUT TO THE TEST AS CHINA CHOKES OFF CRITICAL MINERAL SUPPLIES

As recently as the 1980s, the U.S. was a key player in the rare earth minerals industry, but price increases led its flagship Mountain Pass mine in California to close in 2000.

China, with its cheap labor, near-nonexistent environmental regulations and cash flow from the government, now controls over 80% of the rare earth minerals market, which is crucial for electronics, defense systems and green energy.

In 2010, China cut off Japan’s access to its mineral market in a diplomatic spat over a fishing trawler and territorial disputes. While not directly impacting the U.S., the move spooked Washington by proving China was willing to use its dominance of the market strategically. It shaped trade talks around tech and minerals – and prompted serious concerns about U.S. dependence on China’s mineral market that have yet to be fully addressed even today.

The incident reframed China in the American mindset – not just as a trading partner, but as a rising strategic competitor. It also sparked broader cooperation between the U.S. and its Indo-Pacific allies.

Since 2023, China has been instituting further crackdowns on mineral exports aimed at hurting the U.S., limiting access to gallium, germanium, antimony, graphite, tungsten and more.

The Obama, Biden and Trump administrations have all moved to prioritize domestic rare earths mining, but the onerous licensing process and environmental regulations mean domestic projects can take decades to get off the ground.

In March 2018, President Trump launched a protracted trade war with China, accusing Beijing of “ripping off” the U.S. and stealing intellectual property. He began by imposing global tariffs of 25% on steel and 10% on aluminum under Section 232, citing national security concerns.

China retaliated with $3 billion in tariffs on U.S. exports like fruit, wine and pork.

Then in April, the U.S. trade representative listed $50 billion in Chinese goods for tariffs under Section 301, citing IP theft and tech transfer.

China responded with tariffs on soybeans, cars and airplanes, and Trump, under pressure from impacted farmers, offered bailouts for the agriculture industry.

The trade war escalated in tit-for-tat fashion, with Trump slapping 25% tariffs on hundreds of billions of dollars’ worth of Chinese goods – and Beijing responding in kind – until tensions eased in 2020.

In January 2020, Trump and Xi signed a “phase one” trade deal where China agreed to increase agricultural purchases by $32 billion over two years, purchase more energy and manufactured goods and improve IP protection and cease forced tech transfers. The U.S., in turn, agreed to suspend new tariffs and roll back some existing ones.

China then doubled down on its “Made in China 2025” strategy, ramping up self-reliance in key sectors like technology and agriculture. Beijing’s central bank stepped in to cushion any economic fallout.

China has long used its massive market leverage to coerce U.S. businesses into compliance – adding indirect pressure to U.S. policy discussions.

Chinese actors have pressured various U.S. companies – Nike, Meta, Disney and the NBA – to toe the line on Taiwan, Hong Kong and the abuse of Uyghurs in the Xinjiang province or risk losing market access.

In 2019, China lashed out at the NBA after the general manager of the Houston Rockets tweeted support for pro-democracy protests in Hong Kong. Beijing swiftly suspended NBA broadcasts and severed ties with the Rockets entirely.

A former Meta employee turned whistleblower, Sarah Wynn-Williams, has alleged that CEO Mark Zuckerberg developed and tested custom censorship tools to offer China in hopes of gaining access to its tightly controlled internet market. A Meta spokesperson has called Wynn-Williams’ claims “divorced from reality” and false.

CLICK HERE TO GET FOX BUSINESS ON THE GO

China has often required tech transfer or joint ventures as the price of doing business within the country, leveraging market access to gain access to intellectual property.

U.S. firms, hungry for Chinese consumers, complied. But the demands gave China enormous economic benefit while weakening U.S. innovation and IP competitiveness.

The practices were the grounds for Trump’s Section 301 investigations, first launched under the first term, that led to tariffs.

Chinese theft of American IP costs between $225 billion and $600 billion annually, according to a 2018 report from the U.S. Trade Representative’s office.